Bamboozled? Getting the facts on Bamboo Textiles

At Fairware we’ve had plenty of interest in apparel with bamboo content. In addition to being easy to care for, soft and silky, bamboo fibers have been loudly touted as the newest and greatest in eco-apparel.

But there are conflicting facts about the environmental attributes of bamboo textiles so we’ve taken a closer look. The following is based on our online research and we welcome your comments, input and suggestions.

Bamboo: The Plant

The premise that bamboo textiles are eco-friendly is largely based on the sustainability merits of the plant. Part of the grass family, bamboo is the fastest growing plant on Earth (giant kelp is second). Instead of taking centuries to mature, like hardwood, bamboo can be harvested after only 3 to 5 years.

Bamboo is also self-sustaining with an extensive root system that sends up new shoots each year. This substantially reduces the need for intense cultivation practices. The large root system also helps prevent soil erosion and improves the water-holding capacity of the watershed. With sufficient rainfall, bamboo crops don’t require irrigation.

Perhaps most impactful is that bamboo can be grown without chemical pesticides and fertilizers. Further, due to its huge biomass above and below ground, a bamboo stand sequesters four times as much carbon as hardwood trees and generates up to 35% more oxygen.

It all sounds fabulous, but like many crops, there are real concerns that some bamboo comes from wild spaces and leads to habitat loss. Similar to cotton, bamboo monocultures are an issue (although there are currently no known GMO variants).

Bamboo: Textile Production

While bamboo appears to be a relatively sustainable crop, with great potential as a carbon sink, an examination of the fabric manufacturing process raises some concerns.

The fibers that make up bamboo textiles are considered regenerated fibers as outlined by the Organic Exchange. This means they are man-made fibers that have been artificially created using natural building blocks (e.g. proteins or cellulose) as opposed to fibers made entirely by nature (e.g. cotton).

There are two ways to process bamboo into a textile: mechanically or chemically.

The mechanical process includes crushing the woody part of the plant and then applying natural enzymes to break the bamboo cell walls, creating a mushy mass. The natural fibers can then be mechanically combed out and spun into yarn. The fabric that results has a similar feel to linen. Very little bamboo material is produced this way since it’s labour intensive and expensive.

Most bamboo fabric is created through a chemical process very similar to the production of rayon from wood or cotton. While there are a number of ways to chemically create rayon, the most common is the viscose process which uses hydrolysis alkalization with multi-phase bleaching.

Through this process, bamboo leaves and shoots are essentially cooked in strong chemical solvents such as sodium hydroxide and carbon disulfide (for a detailed explanation of the process, see this fantastic post). Once cooked, the resulting liquid is pushed through tiny holes (a spinnarette) directly into a chemical bath of sulfuric acid where it hardens into fine strands. After being washed and bleached these strands form rayon yarn which can be dyed and woven into a soft silky fabric correctly referred to as “rayon from bamboo”.

Chemicals: concerns for the environment and occupational health and safety

As described, the majority of bamboo textiles are created through a chemically intense process. If not correctly managed, these chemicals pose a risk to workers’ health. Sodium hydroxide can cause irritation of the skin and eyes while carbon disulfide and sulfuric acid have been linked to neural disorders and respiratory problems respectively. Similarly, poor management of effluents can cause serious damage to the surrounding environment.

Bamboo Labeling: “Rayon from Bamboo”

In response to the over-zealousness of companies to market bamboo textiles as super-eco and generally awesome, in the past year both the Competition Bureau of Canada and United States Federal Trade Commission have dealt with the issue of accurately labeling textile articles derived from bamboo.

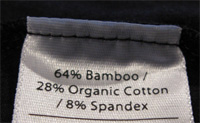

In Canada, this has resulted in guidelines which require that all textiles containing bamboo be labeled according to the chemical process through which they are produced. For example, “rayon from bamboo” as opposed to simply “bamboo”. Further, performance and environmental claims, such as “naturally antimicrobial” or “biodegradable”, must be supported by adequate testing.

In the U.S. this has been taken a step further with a number of companies being charged with “bamboo-zling” consumers. In 2009, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) charged four sellers of clothing and textile products with deceptively labeling and advertising items as made of bamboo, when they were made of rayon. The FTC also charged the companies with making false and unsubstantiated “green” claims. Among these, that their bamboo products were manufactured with an environmentally-friendly process, that they retained the natural antimicrobial properties of the bamboo plant and that they were biodegradable.

Bamboo Textile Certification

To address both environmental and worker-safety concerns many factories that produce bamboo clothing get certificates verifying their practices and products.

Product Certification: There are a number of textile certification schemes (something we’ll explore in greater detail in a future post). A common one is the Oeko Tex Standard 100. OekoTex aims to demonstrate that there are no harmful chemicals in the finished fiber. However, this standard only examines the final product and doesn’t consider chemical usage during the processing of the fiber.

Factory Certification: There are myriad factory certification schemes such as ISO 14001, which shows the factory has put in place an environmental management system to green its practices, or the SA 8000 program, which stipulates social accountability standards but not environmental ones.

As Siel points out, ISO and SA certifications are generally meant for business-to-business use and not consumer education, making it difficult for the average person to know if a bamboo garment comes from a certified facility.

Some good news – improved bamboo textile production

The good news is that some facilities have started using more benign technologies to chemically-manufacture bamboo fibers. The process used to produce lyocell from wood cellulose can be modified to use bamboo cellulose. In addition to using less toxic chemicals, the bamboo can be processed in a closed loop system whereby 99.5% of the chemicals are captured and recycled to be used again. The lyocell process is also used to manufacture TENCEL®, a fabric used by Patagonia among others.

Cutting through the greenwash – advantages, disadvantages and potential

Upon closer consideration, it’s clear that bamboo derived textiles aren’t the silver bullet of eco-apparel and moves by labeling enforcement bodies to reduce the greenwash are well justified. At the same time, writing off bamboo fibers completely may not be warranted – clearly there are advantages and disadvantages to bamboo.

Further, when considering the alternatives, no fabric is perfect. Polyesters and acrylics are fossil fuel based and require plenty of water, chemicals and energy to produce. Cotton is available in both conventional and organic versions, but both are water- and cultivation-intensive crops featuring genetically modified monocultures.

Is it possible that bamboo-based textiles may still be coming into their full potential? With increased interest in the environmental attributes of bamboo-based fabrics, it seems cleaner production processes are appearing (e.g. lyocell process). In addition, labeling enforcement bodies seem increasingly interested in the representation and transparency of bamboo fibers. Perhaps this could lead to advances in applicable environmental and labour certifications for both the products and factories manufacturing them.